THREE YEARS AGO — COVID-19.

THE WORLD WAS SHUTTING DOWN.

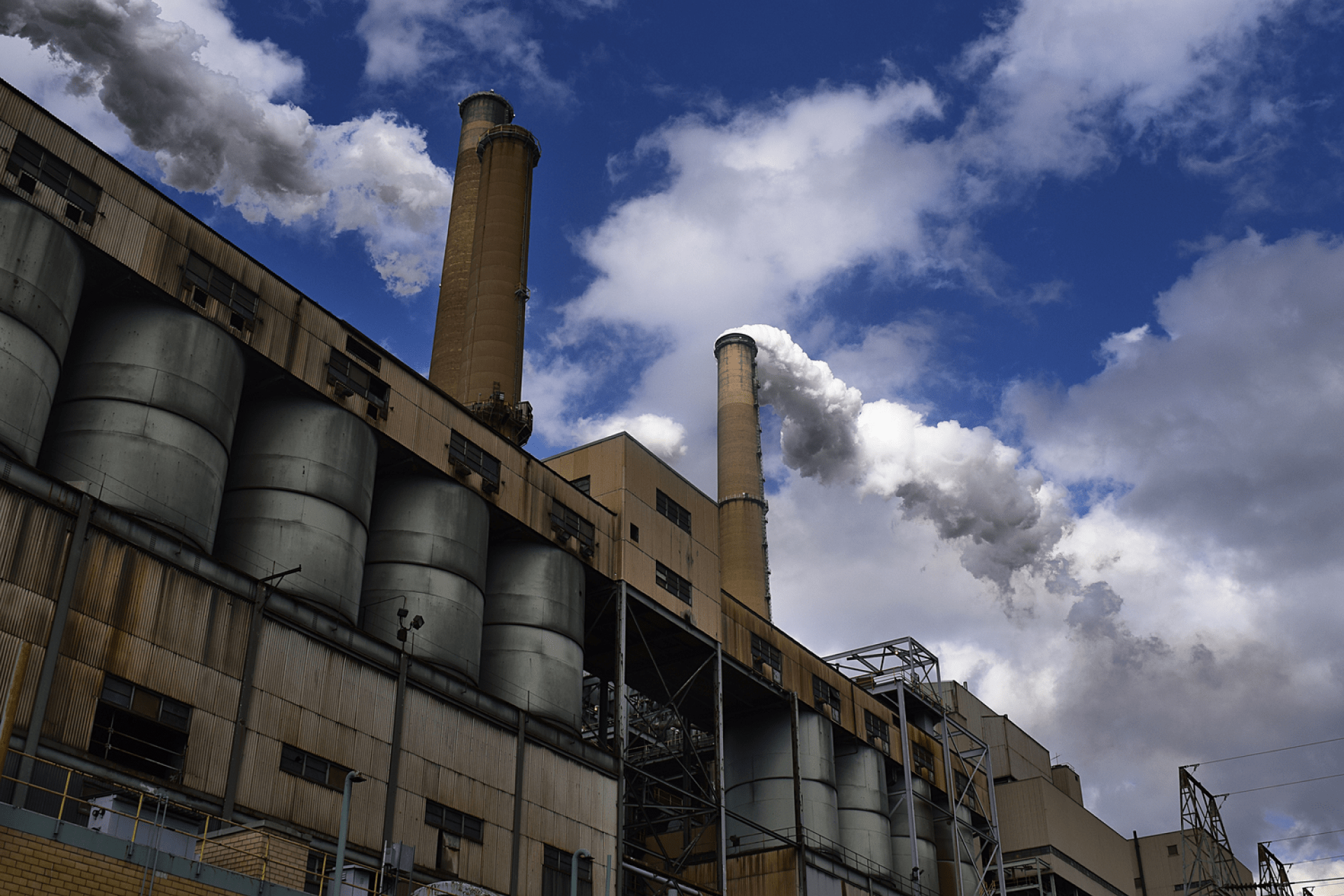

AEP CONESVILLE COAL-FIRED POWER PLANT STOPPED PRODUCING ELECTRICITY A MONTH AHEAD OF SCHEDULE.

Please complete all fields below.

Pomerene Center for the Arts

Anne Cornell

Tom Dugdale

Michael Schmidt

OBLSK

FORT

Pomerene Center for the Arts

Community Arts Fund at the Coshocton Foundation established by Robert and Caroline Simpson

Ohio Arts Council, ArtsNEXT grant

OSU Barbara and Sheldon Pinchuk Community Engagement Award

Ohio State Office of Research, Battelle Engineering Technology and Human Affairs (BETHA) Endowment

Sustainability Institute at Ohio State

TRUCKER: I am standing here as a dad, a dad and a trucker. My dad was a trucker, I have two sons who are both truckers. We truckers were around when you were born in the Conesville river bottoms. We have been watching you since you were young and growing — which makes us, I guess, a sort of dad to you.

I think that’s why I’ve been asked to talk about your history.

From the start, you were a hub, connecting this little rural part of Ohio to the world. You were a hub and we truckers were your grapevine. They said at the time there was a trucker on every corner.

We came in and out, brought you things and took things away. We watched and talked while we waited, sometimes in long lines to load or unload… We had a bird’s eye view of what was happening.

When you came on the scene, it wasn’t you by yourself in the river bottoms — it was you with huge 5000-acre reserves, and the company owned all of it. They owned the reserves, they owned the coal, they owned the transmission lines, and of course, they owned you. Everything. If you go to the ODNR website and look up AEP Coal Lands, or any of the surrounding reserves — those were all surface and deep mines. It took a lot of coal to keep you fed. 100 tons every 8 minutes.

I’d like to read this Short List of Things You Needed.

1. Coal obviously. We truckers brought you coal, but not so much until the 80’s. Most of your coal came by conveyor at first from as far out as Otsego and Plainfield.

2. A load of limestone for your first shed. And so much more limestone after that.

3. Materials to mix concrete on site, for the times the job was too big to haul ready-mix truck by truck.

4. Parts for your parts. For over 6 months, we were trucking in parts for the Coal Chief and the Broken Arrow dragline. Huge digging/swinging/dumping machines to feed the hungry you.

5. So many funny small things. Once I borrowed my boss’s Cadillac to go to Cleveland to pick up 4 custom bolts. And once, I don’t remember what you needed, all I remember was saying, “Hell, I’ll just take my motorcycle!”

6. Overloaded illegal loads, like a 43,000-pound blower hauled from Charleston, West Virginia, during a snowstorm. It wouldn’t balance on the flatbed without being cantilevered way far out to one side. It needed to be installed before 6am — I forget on which unit. It wasn’t the best situation, but it had to be done. So we done it.

7. Sometimes you just needed us to move things around the plant. When it got really cold, we’d spend the night hauling frozen coal from the hoppers to the crusher so it could be blown into the burners. It was a good winter job with lots of hard shoveling. Folks mistakenly think of truckers as sitters. It’s not only miners that get black lung from coal dust.

Next short list: Things You Didn’t Need (that you needed us to take away).

1. A field of corn that needed to be harvested so they could break ground. It was too wet to bring in equipment, so my dad helped the farmer husk that corn by hand.

2. A massive amount of logs when the Tri Valley Reserves was cleared for mining — largest timber harvest east of the Mississippi. Logs to the mills, wood chips to the paper mills. There were three paper mills in Coshocton at the time.

3. Fiberglass debris from a collapsed water tower. I felt the particles in my throat and lungs, so I put on my white chemical suit and respirator. You had to know to protect yourself back then.

4. Which reminds me of the fly ash we hauled and piled up against two high walls. They leaked toxic runoff, but the base from the one neutralized the acid from the other, so I guess it worked.

5. We hauled out a mountain of coal ash to a dump off SR 83. We watched them put a PVC liner under the whole darn thing. The PVC came in big rolls like carpet and two women sweated for days, soaked through, to seal it. And we’re hauling again out of your old ponds, making a second mountain behind the first.

Which brings us to my last list: People We Saw, People We Knew.

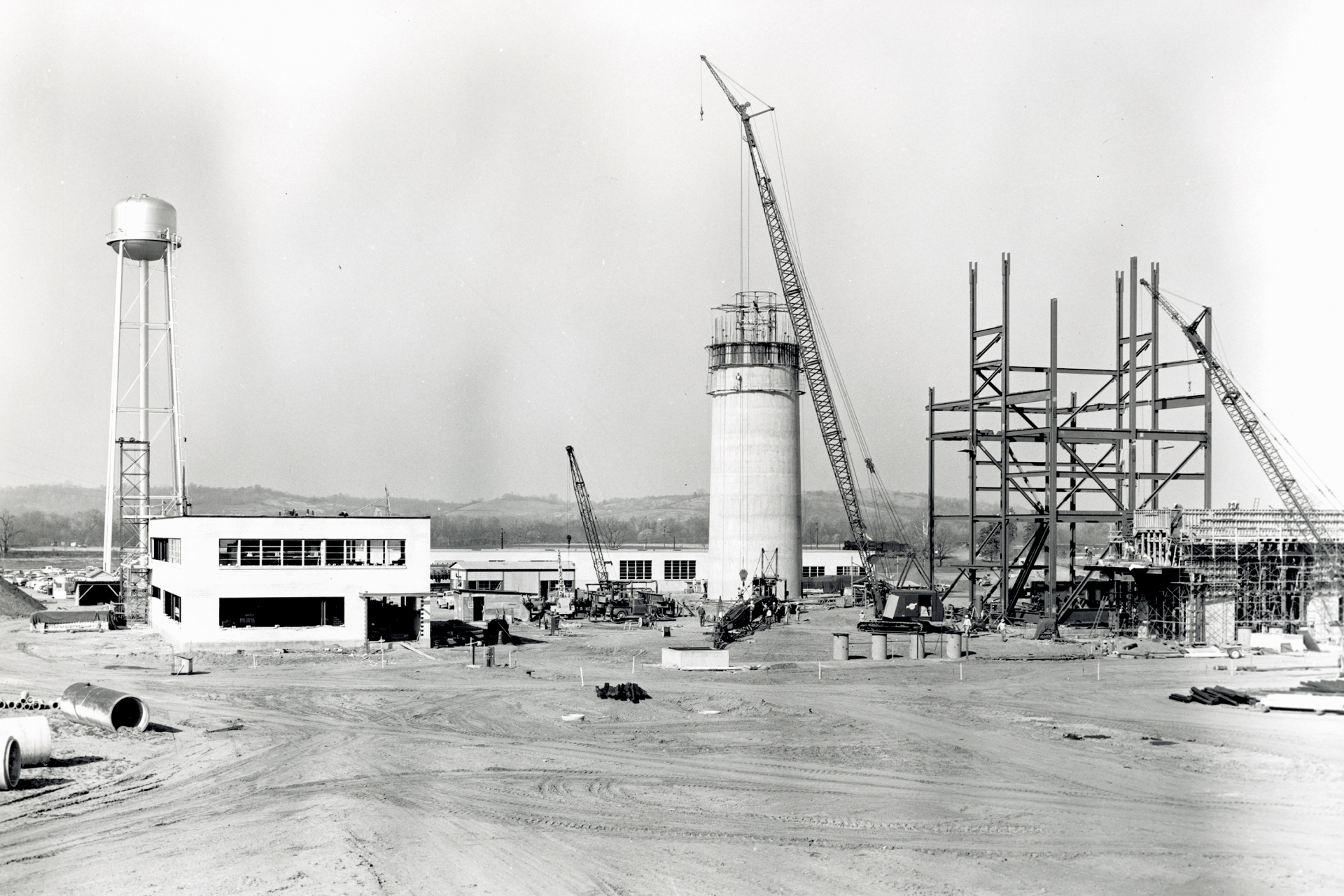

All the contractors and project managers, many coming from out of state, to build you.

All the people that hung off you, like spiders, keeping you going. Putting up lights or — like the Hungarian Team from New Jersey — painting your conveyors.

The guys that came in with probes hanging off their trucks. We called them the Beverly Hillbillies. They were in charge of testing emissions every 6 months until automatic monitors were installed on your stacks to sample every 6 seconds.

A crazy number of 600 employees, when all 6 units were running. 600, until units 1 & 2, and then 5 & 6, shut down and the numbers began dropping. It started feeling personal when the yard birds we saw everyday got forced out —this guy pushed to early retirement, and then that guy, until it was down to a skeleton crew. We brought in fewer trucks, less coal, less limestone for the scrubbers…

(a breath)

Ever since the #4 stack went up, I wondered what things looked like from up there, high on top. At the end, a buddy of mine who worked in the plant asked if he could take me up. His boss was like, “Yeah whatever, we’re shutting down, what do we care?”

I know this community so well from down here. Once I got up there, it all looked…flat. High walls, hills, valleys… Every bit of it looked flat. And that was it.

(a breath)

We’re more like undertakers now. As we haul things out, we watch a team pick you apart like Third World scavengers. Wherever they’re from — they must not have much of a life at home. As we haul things out…we talk… forever your grapevine. Though we can’t say you’re much of a hub anymore.

May you rest in peace.

AEP SUPERVISOR: Like so many of us, I spent my entire career at the plant. I started on the floor and worked my way up into management. No matter where I was working — and I worked all around — no matter what I was doing — there wasn’t a day when I walked into the heat and the noise that it didn’t feel right.

With all this experience under my belt, there aren’t many “first times” anymore. But here I am stand-ing, first time, in front of you, ready to deliver a eulogy.

I thought I’d start with this quote by Henry Ford. It’s the same way Ford’s eulogy started. Here it is: “There is too much to do in a day to spend minutes of it in the futility of grief.”

This quote goes well with what I want to talk about, which is not grief, but The Great Work of the Plant.

At our peak we put out 2000 megawatts. That’s a lot. That’s electricity for 2 million homes. That’s more than twice the size of Columbus. That’s a fifth or a sixth of all Ohio. That’s a lot of lights, laun-dry machines running, houses heated and cooled, and now, these days, a lot of devices charged.

I’m not sure the lay person understands much of the process or much about the product. You can’t see it. You can’t store it. It is hardly a thing, these electrons flowing through the wires, constantly dis-tributed over a volatile marketplace.

All the perfections and complex processes:

So much effort… All you had to do was look at the miles and miles of tubing carrying water and steam and oxygen through the plant to appreciate the miles and miles of potential leaks and breaks. That alone was enough to make what we did feel like magic. Inside supercritical Unit 4, steam was compressed to such a degree that it behaved like liquid… It was gas, vapor, but it acted like liquid. Wrap your mind around that magic.

Every day, in the face of danger, we worked together to make this magical stuff. We didn’t ask,

“Why?” “What for?” We were making something people need. There was pride in the monumental power and importance of it all — so much pride in this rural workforce led by managers who had vision.

I’d say the vision thing began big time after a nasty strike, when AEP bought the plant and Dan Lambert came on board. We started having all these meetings thinking not just about equipment and stuff, but about our people. If we were going to grow, we needed people prepared to work together using new strategies and more sophisticated science.

Dan Lambert saw the link between good community relations and good labor relations. He was cru-cial in us adopting the elementary school across the river. Employees from every level got involved over there with parents, kids, teachers — we did it right. When our environmental people gave tours to kids, they weren’t just explaining — they were sharing, and excited about it. We sent a team to Washington DC to present our adopt- a-school program. A 4th grade kid built a computer, start to finish, while the adults explained to a congressional committee how our partnership worked.

We won some significant recognition for that. But even better, we made a difference. Every day.

It might sound naive and overly proud, but this is how industry and labor and management and community are supposed to work. Not to leave government out of the equation, though, because we did get significant government dollars through grants. We all pushed the boundaries together.

And there was creativity. We’d get a directive from above, and we’d say, “Well just how do they expect us to do that?” But then slowly but surely, working together, we would figure it out. We could’ve just rolled over of course, said “Nothing we can do,” but we always kept going. Corporate told us we were like survivors on the deck of a burning ship.

This particular story sticks out — Ryan Forbes, just a young guy at the time, came up with a method to pipe limestone slurry from Unit 4 to Units 5 & 6, which were still using expensive processed lime from Kentucky. It was risky, really risky. Nothing like it had ever been done before.

Corporate said, “No. Don’t do it.” Corporate thought that plant was theirs, it wasn’t. It was ours. They received the revenue, but the plant was ours.

So we looked at what we had to lose and what we had to gain, and we chose to put a million from our own operating budget towards adapting the system just like Ryan said. You can’t imagine the triumph when it worked! We ended up saving $6-8 million a year on lime! We made a name for our-selves.

When we closed, an executive vice president said, “You guys probably extended the life of this power plant at least 5 years, if not more.”

The Chinese used to come, not to look at how we made electricity, but to see how we were protecting the environment. It’s something they’re trying to figure out. We talked through translators, and I was like, “Oh my gosh. I thought we had problems.”

Our plant was a model for AEP. But in the end, there was just too much stacked against us.

I tell young people, “You’re living in a pristine environment here in the U.S. of A. You just don’t know it.” The United States is going the clean route. Maybe we’re going to be extinct, but the planet is going to be fine.

Amen.

RESIDENT: My people came here from the Steubenville area. There’s a coke plant across the river in Follansbee, West Virginia. I had relatives there for a long time. When I visited, it didn’t matter if it was in the winter, summer, spring — I’d smell that coke burning. And for the longest time, I always thought that was the most miserable stench ever. But the old timers would say, “There will come a time when you’ll appreciate that smell.” Because it meant jobs. It meant industry. It meant a vibrant community. I bring it up because your stacks meant jobs – high wage jobs. We all were thinking of the employees the day they shut you down.

Your stacks also meant home. You could be up to thirty or forty miles away at certain points when you saw those stacks. Even my three-year-old great grandson, when he’d see your stacks, he’s like, “Oh, that’s home!” That strikes close. I think that’s what we all look forward to in our daily lives — getting home. We knew where we were, when we saw your stacks. The world knew where we were, when they saw your stacks.

Conesville Power Plant Ohio Power Co., Conesville Power Plant Columbus Southern Ohio Electric Co., Conesville Power Plant AEP.

It feels important to name you, Neighbor. You were huge.

At the end of the day, you were the life and blood of the community, or a big piece of it.

Maybe we complained some. When you started up, we couldn’t hang laundry without coal ash putting brown marks and little holes in the sheets. The company hung buckets in town to collect the ash — “data” they called it. Seems pretty darn primitive now.

It’s hard to wrap your head around all the changes that happened during your lifetime. You’d think at this point we would be adjusting to this constant pace of change. But we’re stuck in a mindset where we do not like change, not even the slightest little bit — it gets resistance. We’re not good at changing things up and going a different direction.

You have to laugh at people’s reactions when they learned what it was going to cost them to have their trash picked up, once the township didn’t get tax revenue from you anymore. Ask anybody outside this township, and they’ll kind of hint that we got a bit spoiled in here.

We hated to see you leave. Even with the things that kept us up — the night coal trains coming through… If you lost a unit and the safety was lifted, you’d wake up the whole village. That sound was something to hear. We strained to hear the names when people were paged over your PA system in the middle of the night. It felt uneasy, like they were being called to the principal’s office.

In Conesville, the cornfields come right up to the edge of our streets like walls. Farmers still look to where your stacks were to see which way the wind is blowing. You were a weather station.

You were also a clock. We knew what time it was just by your sounds. Some things we could hear all hours — the conveyor belt going, the dozers clinking… It was crazy, even up at Wills Creek you’d be fishing or on a kayak down by the dam, or in the woods with the hills in the way — and you’d still hear all those noises. And now you don’t hear any.

And there’s the dark.

I used to tell people who came to visit overnight, “Look out. See all those lights? That’s our mall.” Malls aren’t even so much a thing anymore.

Like a mall, you brought people to town. Floods of people during shutdown. Forget getting into the Conesville Store during shutdown without a long wait.

I sat on my patio and watched stack # 4 go up in a continuous 24-hour pour — and I sat on my patio and watched the stacks come crashing down. You should have felt the ground. The dust was unbe-lievable. Bits, like pieces of sand, came right through my screen.

I guarantee that anybody living in Conesville still has a black coating of soot in the attic, and who knows what it’s meant breathing all that in over the years…

There are people who wish the company had bought up all our houses for three-and-a-half times their value, like they did in Chesire down along the river. There was a lot of cancer there. I mean,

I don’t know. I’m not a medical… I’m not gonna go down a path that I don’t know. But in 2019 the kids had to stop drinking the school water for a while because of mercury. Seems like you’re hearing a lot about mercury and the EPA and how they had a lot to do with the end.

Even though you were outside the limits, we thought of you as inside the village… You were a good neighbor, and not just because of the Township taxes you paid, or the 50/50 split to chip and seal our roads. But also — little things, caring things, like somebody from the plant dressed up as a lightbulb handing out candy apples for trick-or-treat. Or how you bussed in a thousand kids for Community Earth Day. Maybe nothing shows it better than how, on your way out, you left us a $60,000 commu-nity/school playground. And it wasn’t just the corporation making a show. Folks in the plant would pass the hat to help each other and the community out.

A couple years ahead as things were shutting down, your CFO and some other officers sat down with the township trustees and said, “This is how it is. We’re going to be leaving, and you need to be thinking ahead. You need to prepare.” And we did, we tried. But it was still devastating. Your depar-ture has had a devastating effect on the community. If there was anything we could have done differ-ent, I don’t know.

Now we’re in transition. But what are we transitioning to?

Buzzfeed sent a photographer to Coshocton County, to do a story about the decline of Appalachia… He takes this shot of a guy drinking beer on his porch without a shirt, and his porch is all falling apart, and a little kid without any clothes standing there… He didn’t capture what we’re about, just the absolute worst things about us. “Oh, poor us, we’re Appalachian.” That’s not us. There’s a lot of misinformation out there, and some of it’s intentional.

Right now, the demolition is part of a progression.

When the stacks came down a door closed. When one door closes another door opens…

SCHOOL ADMINISTRATOR: Back in the 70’s my Dad made what today would be $250,000 operating equipment in the mines. He made a lot of money, but by the time he was 55, his back and legs were trashed from the constant climbing and lifting, and he had to retire. He didn’t want that for me. He wanted me to have an education.

I’m an educator. I don’t make near the money he made.

If the truckers were like dads in all of this, we can think of River View School District as your child.

We graduated our first senior class eight years after your first unit went online. This was before my time, and not everything was perfect. Dick and Jane readers were still being used. The old schools were heated with coal. You hear stories about mornings when the halls would be so full of smoke you couldn’t see. But we fixed that. We’ve fixed so much over the years. It’s been a source of pride, how well we’ve maintained these old buildings. We’ve always been Black Bear Proud.

Because you provided, we could provide. We were proud that we could provide.

When our teachers and administrators asked for books, they got books. When they wanted to go on fieldtrips, we sent them. We were able to hire full-time support staff and give them benefits. We pro-vided stability and community led by our anchor families — People wanted to be part of the River View District.

If I were going to give advice to the Harrison Centrals of the world, newly flush with fracking dollars and new state-of-the-art athletic facilities—all turf track-and-fields — baseball, football, softball — the best of the best… I’d say, “If you have the ability to invest for the future, put your plan in place so you can give back to the coming generations and not end up right back where you used to be, in spite of all the coal that came out of your hills.” The 60’s and 70’s were heady times in Coshocton County. River View High School was built for 1000 students in anticipation of an expanding student body. Manufacturing was growing. We were building a strong blue- collar community. In 1980 we built a Junior High from cash we had in reserve. When you build a state-of-the- art school with cash, the taxpayer gets a distorted view of public edu-cation funding. Take a look at our history of passing levies and look no further.

In the 60 years since, everything has switched, everything’s reversed, and now you’ve got a local school district that is struggling. The elementary school in Conesville is closing. So is the one in Keene. Union and Pleasant Valley and Roscoe already closed. We’re shrinking, we’re contracting, and we feel it.

You’re gone.

I remember attending a community meeting. Dan Lambert, your plant manager, was there. After hearing from teachers at that meeting how hard it was to keep students engaged in science, Dan pulled Management and Labor together back at the plant and said, “Let’s adopt Conesville Elementary. We can give them the science they need.” This was a game-changer. Classes visited the plant. Guys from the plant visited the school. Together with parents and teachers, they cleaned out a stor-age room and installed a science center. They secured grants together. The state noticed. Governor Taft’s wife visited the school.

Once, AEP employees drove equipment across the river to help plant 50 trees the school had won in a competition — 48 are still living. I love that! We were all proud. Kids felt important. You were a great partner in education.

I remember something else from that meeting. Maybe something more important to us tonight than anything else. Dan Lambert talked about the future. “The world we work in,” he said, “everything is changing. We have to adapt. We have to learn to live with change. I think of it like making a movie that’s got its particular challenges. You ask, what are the challenges? Who do we need to meet those challenges? Then you assemble the best team possible — actors, film crew, composer, set designers — and after a lot of hard work you have a movie with a long list of credits. Then everybody resets and takes a new part and gets into a new configuration to make the next movie.”

What does pulling together in the face of change look like for us? What does growth and stability look like? What does Coshocton County look like if every high school graduate and every alum with a certificate or college degree could get a job offer here in the County?

Like all of us who understand our parents are mortal, we knew your life would end one day. But what human being is not taken by surprise when death becomes real? It’s been hard.

Tonight, as we mourn the loss of AEP Conesville, Conesville Elementary, and Keene Elementary, let’s also celebrate. In the face of our current challenges, let’s celebrate our potential to build new teams of teachers, with parents and a committed community all working together in support of each other — and most importantly — in support of our children.

This is our time to pull together in a new configuration. We are and remain Black Bear Proud.

BROTHER 1: Our plant closed in 2020. Was it in the spring? Yes, at the same time as the pandemic. It’s hard for me to even separate what we went through because both things were huge. It was so hard to put things in perspective because there was COVID-19 on top of everything. Right? It was barely survival.

BROTHER 2: The last day was supposed to be May 30th but COVID moved the date up, and I got-ta tell you — that was hard. Not just for those who were sent home that day, it was hard for those already gone. Cuz it was your livelihood, you know? Your life. It’s what you did. Every day.

BROTHER 3: This eulogy is for the loss of our brothers and sisters, for what we gave each other.

BROTHER 2: When the stacks came down, there were those standing there that it really meant some-thing to, and then there were people who were there for the spectacle. This eulogy is not for you if you’re here for a spectacle. It’s not for the hobnobbers who might give a bunch of words, but haven’t been affected like the people who lost their jobs, got divorced — whose whole world changed. Those who really got hit hard.

BROTHER 3: If you care — this eulogy is for you. This performance is for you.

BROTHER 2: But mostly, it’s for the hundreds of us that worked together to keep the lights on and energy flowing from the Conesville Coal-fired Power Plant.

BROTHER 1 and BROTHER 3: (in solidarity) Yes.

BROTHER 1 Brotherhood was a big part of it — I think that’s been the hardest thing for me to tran-sition from. We were all friends, close-knit. We hung out together, raised our kids together, went to ball games together. We had parties together, spent Christmases together… You know, we did everything.

BROTHER 3: I talk to people at the job where I work now, but you’re talking to them about business. It’s all business. It’s not come in first thing in the morning, have a cup of coffee, bullshitting about what your kids did last night or what your plans were for the weekend. There was a really nice com-munal aspect to the Plant that I don’t have anymore. What passes as conversation now is me trying to keep up with these people I work with — It’s been a very, very lonely transition.

BROTHER 2: Working at the power plant was a good time. Mostly we had that kind of nose-to-the-grindstone, hardworking, almost competition kind of thing, to see if you can work more hours in a week than the guy next to you. When you step back, it was insanity, because we’d get to the point where we’d deprive ourselves of our own free time. We put it in our head that not only is this nor-mal, but I’m doing really good by doing 80 hours this week — you know, I’m killing it… Not just a few people lost their families that way. Ended up divorced because they were working all the time.

BROTHER 1: I stayed married, but I’ll admit there were times when I turned into an asshole. When you’re tired, shit comes out, and you say wrong stuff and offend people.

BROTHER 3: Talk would get pretty rough in the plant. We tore each other up. The first time I joined my regional traveling group, everybody was yelling. I just put my head down and said, “OK.” It was rough, but you learned to give it back. That’s how it gets. There was a bit of show about it. You had to sharpen your wits and get good at timing.

BROTHER 2: But we loved each other like brothers. That’s how it is when you work together twelve hours a day. Hardly a woman on the floor — it was probably hell for the women that were there. They had to work two, three times as hard just to prove themselves. I’m sure they knew they were shaking up the fraternity. It makes me feel bad, thinking back on it.

BROTHER 1: We trusted each other with our lives because there was bad stuff that could happen. Two guys I know were killed. People were injured. We got way better in the latter years, but it was typical in the industry.

BROTHER 2: You get complacent around all this equipment because you’re so used to it. But you’re walking by stuff that — if something went wrong — you’d be a dead man.

BROTHER 1: Being your brother’s keeper was an assignment.

BROTHER 3: It was kind of like the military, in a way. You had to follow all these procedures that slow you down on purpose, so you wouldn’t wreck things or people in your effort to solve a prob-lem.

BROTHER 1: Your life’s on the line. They pay you well because your life is on the line.

BROTHER 2: For a while they paid incentive money if your team didn’t have a safety incident.

BROTHER 1: So of course you’d bury some stuff.

BROTHER 3: “Be a sport, don’t report.”

BROTHER 2: They didn’t truly want to hear it anyway. I wanted to go to Columbus to let the CEO know that what they read — and what actually happened — was two different things.

BROTHER 1: We’re all human, we’re all fallible.

BROTHER 2: I carry a sort of permanent map of burns on my body. I can tell you where in the plant I got each of them — As structure after structure falls to the demolition, my memory starts to go. I’m worried there’ll be a time when I don’t remember the exact locations anymore…

BROTHER 3: It’s funny, last night, I made a list of all the names I could remember. I could name you over 200 guys. There’s so many more. I can remember faces, but I just wish I could remember the names.

BROTHER 1: The Facebook memory page is full of obituaries.

BROTHER 2: I used to only know of one person with brain cancer. Now I know nine or ten. Your tooth enamel contains a kind of chemical record of the climate and conditions you grew up in. When they dig us up and look at our teeth, do you think they’ll notice we worked together?

BROTHER : We breathed in more flue gas than you’d care to know. Way more than anyone on the outside was ever exposed to. And here we are. Says something doesn’t it?

BROTHER 1: We tried to make it better. So many changes we made over the years at the plant was for burning cleaner and cleaner.

BROTHER 2: I’m not so sure coal has that big of an impact on the environment. I could probably argue that back and forth, left and right.

BROTHER 3: The units were old, they weren’t designed to hit all those clean goals.

BROTHER 1: I find it difficult for the United States to clean its act up when other countries keep burning coal. Somehow or another, with the earth turning and the air moving, I got to think we prob-ably breathe polluted air that was at one time over China.

BROTHER 1: We’re pro-fossil fuel energy people. Pro coal, pro-oil and gas. Not so much out of choice — but where’s our pro-baseball team to stimulate our economy, you know? Where’s our chip factory? I don’t feel like our handicap has ever really been taken into consideration. Coal was an opportunity, so we took advantage of it, just like anybody else would. It made the economy run, ours and yours.

BROTHER 1: When I started there were over 600 people employed at the Conesville station. When units 1 & 2 shut down forty years later, we got down to 250. Lots of people went then. It was terri-ble. It made you have sleepless nights. I had two teenage children. It made me think, “What are my kids going to do?” Scared the crap out of me. Those were the lean years…. Define, measure, analyze, improve, and control…. We saw it as lean the people out at the bottom. Not a good Jenga strategy. Everybody pulled together to make it work with less people, we kept doing it with less and less, but it wasn’t good enough.

BROTHER 3: There were the guys who agreed to go on the road to save their jobs. Saves your job but it kills your family, unless you’re dragging everyone with you in the camper —

BROTHER 1: Which might also kill your family!

BROTHER 2: A lot of people would say, “Oh well, these guys can get jobs anywhere, they can go some place else.” I didn’t want to do that — I liked this region and didn’t want to move out of it.

BROTHER 1: It was a way to run a company, but it was no way to treat people.

BROTHER 3: Always in the back of my head was the fact that I was working for this dying thing, that had just a couple more months to live. Coal prices and natural gas prices had a lot to do with it, if you ask me.

BROTHER 2: People say there’s jobs here, but they’re not the same kind of jobs. The good jobs are few, and it’s hard to get one. And the people aren’t the same.

BROTHER 3: Not long after the plant closed, me and my boss talked about how we missed it al-ready. I said it’s kind of like a high, what we did. And he was like, “It is a high, it’s unlike anything you’ll ever do in your life, and trying to explain that to people outside — I’m not sure most of em can grasp what we mean.” I think about that a lot, still being young. Will I ever find something equal to this?

BROTHER 2: If something’s gonna happen good out of this — provided people want to see good out of it — I suggest we have something where we can go and talk. Just talk and be together. Even if it’s just a couple hours, even if it’s just a few guys. For a lot of us, I think that would go a long way to-wards helping us move forward. Brothers.

BROTHER 1 and BROTHER 3: (in solidarity) Brothers.

PASTOR: Three years after the last electricity was generated and transmitted from AEP Conesville, we meet in this place for a moment.

We meet here in a moment of fellowship to speak and listen and witness that we are not alone but part of a common world of feeling. Those who have spoken before me have so eloquently given shape to the life of the plant, its history, the great work done, and what it meant to the community.

I hope — to borrow from William Shakespeare — “to give our sorrow words.”

It’s been three years since they blew the steam off Unit 4 for the last time. Unlike shutting down for maintenance, this final release was like a last breath. A death rattle that let us all know it was done. Only quiet and dark… Such a strange feeling then — this giant, sitting there in the pitch dark.

This loss is not Coshocton’s first. Before AEP Conesville there was West-Rock before that, Novelty before that Pretty Products, Steel Ceilings, Ansell Edmont, Shaw Barton/JII, GE. All closed. Work-ers dispersed. Empty pockets. Upheaval. But all these deaths do not make this one easier. To say there’ve been deaths before doesn’t lessen the grief here. People say things like, “It will hurt less over time, we’ve got to move on,” but those words do not reach our hearts. We need words that reach our hearts.

“The grief that does not speak knits up the o-er wrought heart and bids it break.”

Thank you, Shakespeare. We’re grieving. A big part of our world has ended. Everything has shifted. It’s not just that we’re resistant to change, that we’re inflexible — It ends up that it’s just plain hard to imagine how things can go on without your team, that the future can occur without you on the job.

My grandmother said more than once, “Don’t throw away knowledge. The rule book was written in blood, and you gotta think about that — about all the stuff that was learned. Things change,” she said, “technologies change, opportunities change, communities change — the basics don’t.”

My question to you is: what are the basics we learned during the life of the plant? What is it we need to be remembering about our lives with AEP Conesville? Memory and the ability to imagine the fu-ture sit in the same place in our brains. It’s a brain thing, a human electrical system thing. We cannot separate one from the other. “Imagining the future is a form of memory” —that’s the title of an article I read, but it pertains here tonight. So I’m asking you, what is it we should be remembering so we can be imagining our future?

I believe we’ve heard some answers right here tonight. Let’s remember that once there was a place where the lucky found themselves as useful members of a community, a state, a nation — their sacri-fices validated by good wages.

Let’s remember how great it felt to work in a place that called on all parts of you — Where you not only worked hard physically, but where you had to think and problem-solve and work as a team.

Let’s remember the visionary leadership and imagine future leaders who will mobilize us in all our imperfections and help us make the impossible possible. Memory and future, together.

Is this not what we want to take with us as a community? The knowledge that when we’re faced with the impossible, when we’re faced with our mortality and imperfections, we should say, “Yes.”

Throughout the history of the plant, from the coal ash falling on clotheslines to its most efficient and cleanest iteration, nobody said, “It would be better to stay dirty, it would be better to keep sending microns of mercury into the atmosphere.” Nobody said, “We shouldn’t be taking care of the environment.”

They said “Yes” until the old system couldn’t be tweaked anymore.

Let’s remember they said “Yes.”

We can do this.

Thank you all for your service.

CHILD 1: Conesville is a really quiet town, not a lot of drama. It was a big event when the stacks came down.

I guess I knew the stacks were coming down, we had been told, but I thought it would be in the after-noon — at least Noon or eleven, when I’d be more awake. It was the weekend. I thought they’d wait until we were out of bed, but they didn’t.

We live in an older two-story house on the main stretch in the center of Conesville. When the stacks started falling, it felt like our foundation was going in. I guess that’s what woke me up. It felt like they were blowing up the house, and we were going down with the stacks. I really thought the house was falling in.

The electricity went off for a minute, and my dog was panicking. I went downstairs holding onto the railing. The dog stuck close — not bounding down the steps as usual. The house was still intact obvi-ously, because I was walking downstairs, but you know what I mean. It was crazy.

In the den, my father was up and jumping from window to window. He was trying to get a good view of what was going on. He’s a taller man, so it was strange seeing him standing on the couch, holding the curtain back with one hand. Then he leaped to the other couch. Back and forth, like a dog or a kid waiting for the UPS man or something. There was a coffee cup on the table, so he must’ve been up having his coffee, waiting to see the stacks come down.

You could walk out on our front porch and get a good view of the stacks, so I opened the front door. I had to rub my eyes. It was a shock that… they were gone. You couldn’t see the stacks anymore. It was very scary.

CHILD 2: Our tree fell down and I saw deers run across the field. The mom deer looked pregnant. The dad deer was pushing her to get away from the stacks. They were running across the field to get away to save their lives.

The tiniest deer was running the fastest. My heart was pounding, and my mom was scared. She said a bad word — She almost never says bad words.

CHILD 3: My mom got scared when the air pushed into the house. Our windows almost shattered because there was a big wave that hit our house, a big air. We could feel the air on our bodies and little rocks hitting you like tiny little pellets.

CHILD 4: The only thing blocking me was a little hill, the train tracks, and a bridge. The smoke came into our house, and I started coughing. We had the windows open. It faded away in a few seconds.

CHILD 5: I was at my grandparents’ house. On the roof. And there was a huge boom. My eyes got really big. It scared my sister so much she started crying and went downstairs and covered herself with a blanket.

CHILD 4: The last stack didn’t go where they wanted it to go. A big metal ring flew off the top into the field.

CHILD 2: Do you think it could have rolled into the village?

CHILD 3: I thought the stack could have fallen on the village. Child 4 I thought they were going to go straight down.

CHILD 3: A siren blared first before they were counting down. They yelled it. 5, 4, 3, 2…

CHILD 1: Afterwards, we went to the field. The stacks were just laying there, hardly anything left of them. It looked like a disaster. We saw the ring.

CHILD 2: My dad worked at the stacks. He climbed inside and cleaned them with a hammer to get the ashes out. He almost fell once and could have died. I’m happy that they’re down.

CHILD 5: My uncle blew them up.

CHILD 4: It sounded like a crash and a tornado mixed —

CHILD 3: It sounded like a ginormous stick snapped while an earthquake was happening —

CHILD 2: It sounded like a giant elephant. Like a stampede of elephants —

CHILD 5: It felt like huge trees falling everywhere —

CHILD 3: Hundreds and hundreds of dynamites blowing things up.

CHILD 1: Loud as a nuclear bomb going off.

CHILD 4: They put bombs in the stacks. My grandpa helped build them. He was a boss. He didn’t watch them come down. He was at his farm. His cow just had a baby.

CHILD 2: My grandpa was just back from surgery on his heart on crutches.

CHILD 3: Our neighbor worked there. He lost his job. Nobody from their house came out to watch, they stayed inside. He’s a drunk.

CHILD 2: You can’t SAY that —

CHILD 3: I was wrapped in a blanket inside my house —

CHILD 1: My dad lost his job. He didn’t work at the plant but his work closed —

CHILD 5: I was in a car eating donuts. People were lined up on the highway.

CHILD 4: My dad said we saw a piece of history.

CHILD 1: Everyone — my brother, my mom, and grandma and grandpa — was recording with their phones — I’ve watched the videos a lot.

CHILD 5: I was in the car with my mom and my dog. I thought my life was going to end, so I started eating as many donuts as I could — inhaling donuts like it was my last meal — and we hit a bump in the car at the same time. The car was vibrating, and I started choking, and the dog wouldn’t stop growling. My mom was scared and took off really fast, and then slammed on the brakes, and I hit my head on the seat. I was knocked out cold, and I had to stay in the hospital for two days with a giant bandage around my head.

CHILD 4: I thought they would come down in little pieces, but they came down all at once and col-lapsed. I told my mom it was like the twin towers coming down. I’ve read a book about that.

CHILD 3: Only the little ones stayed up. We still don’t know what they’re going to do with those. Do you know?

CHILD 4: They took the big ones down to keep planes from crashing into them. Plus empty buildings make good places for people to hide from the cops.

CHILD 2: Now that they’re down, I won’t know when I’m close to my house.

CHILD 3: We went by a couple days later. Trucks were in there cleaning all the stuff out. There were excavators. My sister loves excavators.

CHILD 2: What if they made the whole entire field into a park? It would be fun if we had more parks close by. Make a fountain in the middle and trees and a stone gate opening and benches around the fountain. Or maybe a dog park.

CHILD 4: The main reason they took everything down was because of COVID.

CHILD 1: My dad said it’s because Obama said something about the smoke stacks and how we should just have solar power and stuff. But what happens if there’s no sun one day, and a city or town doesn’t have any power?

That’s what I’m wondering. What happens then?

CHILD 3: I’m pretty sure they’re taking things down to build something new.

CHILD 5: People aren’t talking any more about it really.